Marketing in Japan

by Max von Beust

Marketing in Japan is often described as one of the big remaining mysteries of marketing worldwide, especially for companies

entering the Japanese market (Melville, 1999). And even though the Japanese consumer market is struggling

at the moment, with low GDP and income growth rates (Worldbank, 2015), a decline in population growth

and an ageing society, the complexities of Japanese marketing are interesting to analyze in light of

worldwide changes in the advertising industry. With the shift to the online world, marketing around the

world is changing and new players evolve.

In order to gain an understanding what this continuous shift towards the online world means for the Japanese

market, it is important to understand core aspects of how marketing worked and works in Japan. In this

new world of marketing, three key areas of marketing have emerged to be the main success factors.

The first, obviously, is the power and the importance of advertising. The most powerful companies in the world nowadays don’t base their business model on natural resources such as oil, but rather focus on monetizing their services by building strong platforms as a basis for advertising outreach. No matter, if we are talking about Google, Facebook or the strong player in the Japanese market, Yahoo, advertising is core to their business.

focus on monetizing their services by building strong platforms

The second aspect is the importance of branding. Branding has always been one of the most relevant parts

of marketing, even more, in the online world, where products are not tangible anymore and the amount

of information inflow is bigger than ever, standing out from the mass and gaining the trust of your customer

has never been more important.

After having reached out to your customer with an ad and gained his or her trust through your known

and well established brand, you will want to deliver your product to the customer and here, the world

of distribution systems comes into play. As Japan has a very unique kind of distribution system, this

aspect might even be more relevant here.

This article will describe and analyze distribution, branding and advertising in the Japanese consumer

market. Well established literature is analyzed and new insights and current information is added in

order to describe the current state of the market, relevant cultural aspects and give an outlook on possible

future market developments. This short paper will only be able to peek into the different segments and

the usage of mainly English sources limits the degree of detail of the insights. Nonetheless, overall

developments and learnings are still of practical relevance.

Distribution in Japan

When examining the distribution system in Japan, the main focus will be on fast moving consumer goods. This chapter gives a short introduction into the retail market from a consumer’s point of view before analyzing the current structure of the supply chain. Changes that have led to the current system will be included in the analysis and an outlook will be given at the end of the chapter.

Consumer Goods Retailing

The consumer goods market in Japan, especially the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market, can be divided into four distinct

categories as the market is not concentrated and firms tend to be domestic (Haddock-Fraser, et al., 2009).

Whereas western markets, such as the US-market show a high dominance of supermarket chains with a market

share of over 90% and very low share (5.5%) for convenience stores (United States Department of Agriculture,

2011), the Japanese market is more balanced. Supermarkets account for about half of the retail sales

volume; convenience stores have a slightly higher market share than department stores at about 25% (METI,

2016). In addition, smaller mom-and-pop stores still account for a high amount of end-customer sales.

Haddock-Fraser et al. point out that supermarkets in Japan, nonetheless, are not directly comparable

to those in western countries as they tend to be smaller in size and have a more restricted assortment

(Haddock-Fraser, et al., 2009). It is also pointed out that the density of convenience stores in Japan

is extremely high, which accommodates for the consumer behavior of mainly shopping perishable goods on

a daily basis (Sato, 2004). In order to facilitate these characteristics and to reach the customer in

the right location, convenience stores are abundant and focus on main commuting flows, as car ownership

in Japan is not at the level of other developed countries, thus, making shops outside of densely populated

areas unattractive (Dargey & Gately, 1999). For the same reason, “mom-and-pop” stores still are able

to survive in Japan.

Nevertheless, the biggest players in the Japanese retail market is the convenience store chain Seven-Eleven

Japan with a market share of 41 % in the convenience store market followed by Lawson (20,5%) and FamilyMart

(19%) as of 2015 (Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd., 2015). In addition to offline retail, most of the convenience

and supermarket chains are now slowly moving into the rapidly expanding online retail segment where they

will meet competition such as Rakuten (80 million users) and Amazon as late movers (Salsberg & Morita,

2012).

Structure of the Supply Chain

As the Japanese retail market seems to be highly complex, with different consumer-facing channels and a large variety of brands and store types, it is to be expected that the supply chain system behind these outlets is not simpler. Indeed, the wholesaling system in Japan is made up of multiple layers where retailers, wholesalers and manufacturers interact (Schmekel & Larke, 2002). Adding to this is presence of possible regional and local wholesalers which then provide goods to the retailer and are willing to go to extremes in order to satisfy customer demand.

willing to go to extremes in order to satisfy customer demand

As this system is highly inefficient and smaller local outlets only managed to add marginal value to the

supply chain, distribution systems in the Japanese market are changing and becoming less fragmented (Larke

& Davies, 2007). Especially the large retail chains that are backed by their parent companies (e.g. Mitsubishi,

Mitsui Bussan, Itochu) are pushing for changes in the system and starting to vertically integrate their

local supply chains.

A classic example of this development can be seen in the case of Seven-Eleven. Their franchise based

model is built upon the core pillars of perfectly functioning IT-Systems and fast and coherent distribution

channels (Nagayama & Weill, 2004). Their integrated approach is not based on channel ownership, but rather

on exclusive cooperation with local partners that feed data into the centralized IT-System and receive

accurate information in return. Different local distribution centers provide storage facilities for specific

types of products (e.g. frozen, cold, warm products) to guarantee speedy and easy delivery (so called

Temperature-Separated Combined Distribution System). In addition, the number of deliveries per day to

the retail stores has been decreasing.

Manufacturers often have to work together with retailers of wholesalers in order to place their products

on the shelves. Direct distribution models are not relevant in the Japanese market. On the contrary,

the changes in the distribution and retail systems in the 1990s have led to a decrease of power of manufacturers

as medium-sized retailers were rising (Dawson & Larke, 2005). Nonetheless, their rise has not led to

unified national supply chains; the regional character of distribution systems in Japan is still intact.

Outlook and Possible Challenges

Although the Japanese distribution model with high complexity and great power of wholesalers has only changed slowly over

time, a development can be seen and the trend of e‑commerce (and, as a subcategory, m-commerce) is about

to lead to changes in the environment. As has been noted earlier, the major retailers have had a late

start into the online world and large online retailers such as Rakuten and Amazon are leading the market

(Salsberg & Morita, 2012) followed by kakaku and Yahoo (Statista, 2015). The e-commerce efforts of the

major retailer cannot be found in the top 10 of the market.

This development has several reasons. Japan has one of the highest internet usage rates worldwide at

93.3% (Worldbank, 2015) and the acceptance of credit card as a secure online payment method is rising

(Euromonitor, 2016). Nonetheless, more Japanese online platforms allow for offline payments in convenience

stores or even at delivery. In addition, the infrastructure and delivery services in Japan guarantee

easy and high quality shipment of products to the end consumers, which is crucial to live up to the market’s

expectations.

From a manufacturer’s and seller’s point of view the new online platforms are highly attractive as they

allow them to reach their customers in a trusted environment without having to deal with the high entry

barriers and complications of the offline retail business (Mehra, 2016). Even though the market conditions

seem to be favorable, it remains to be seen if online platforms will be able to gain a substantial market

share in the Japanese market.

Should these platforms be able to get a foot in the door and compete with offline retailers in the long

term, it can be expected that the distribution system as a whole will start changing. Not only will the

amount of intermediaries that stand between the platform or delivery facilitator and the manufacturer

be reduced due to price pressures that occur online, but a move to strongly integrate vertically into

the delivery segment by these online platforms would be far from surprising, as seen in the US (Palladino,

2016).

Branding in Japan

After having analyzed the distribution system, the following chapter will now highlight how products and services are marketed to the customer or consumer. First, the patterns of branding in the market and the motivations behind and reasons for these patterns will be described. Afterwards, further explanations for this behavior will be analyzed by looking at cultural reasons.

Strategic Branding Priorities

The scarce English literature that is available on the field of branding in Japan approaches the topic by comparing the East-Asian

system with the Western branding approach. Different areas such as consumer perception, market pressures

and company-internal structures are analyzed to find reasons for the clear difference between the different

regions.

The main difference between branding in Japan and in Western markets is the clear dominance and reinforcement

of corporate brands throughout the company’s product portfolio (Tanaka, 1993). Authors argue that this

difference can be attributed to the microenvironment of Japan with its history of strong corporate brands,

history, culture and distribution systems.

More relevant, Tanaka argues that different priorities in Japanese companies are the main reason for

this choice. Japanese companies have long shown a preference for measuring success in terms of market

share and that launching new products with very short product life-cycles would help them succeed in

achieving this goal (Wharton, 2007). Western companies, on the other hand, had their focus on sustaining

product life-cycles and gaining profits. Long life-cycles allow for the creation of stable and, thus,

long living and self-sustaining brands. In contrast, a rapid succession for new product releases dilutes

a brand. As a logical consequence, the only asset of stability in terms of branding is the corporate

brand.

Japanese companies have long shown a preference for measuring success in terms of market share

A similar development of corporate brands can be seen in fast moving markets in the western world as well.

Companies in the IT-industry have a strong focus on their umbrella brands as this allows for a great

amount of experimentation (e.g. Google, Amazon). On the other hand, should a company have built a strong

brand, they are happy to push this sub brand without the umbrella — this is especially true for recent

acquisitions (e.g. WhatsApp, Instagram, YouTube, Nest). So, one could argue that Japanese companies mainly

adapt to their market environment when using corporate brands, as the FMCG market actually is fast moving

in Japan.

Souiden at al. propose a further strategic reason for the choice of corporate branding by mentioning

the internal corporate structure (Souiden, et al., 2006). It is argued that the pyramidal organizational

structure within the organization will lead to an orientation towards the top, thus, the corporate brand,

whereas western companies tend to have a product-based organizational structure where brands are independent

from the corporate brand. Although this argument is supported by other Japanese authors (Tanaka and Iwamura)

no final conclusion could be drawn.

Consumers and Branding Choices

No matter the strategic objectives of the companies, the customer is the one who will buy the product and most probably has

the biggest influence on branding choices of corporations. Here, Tanaka argues that Japanese customers

tend to base their decision making on familiarity with a product rather than the direct reward or benefit

(Tanaka, 1993). Familiarity is a clear sign of trust and quality in a product or brand — and the more

often products are released, the more essential a brand will become to support the customer in the decision

making process (Souiden, et al., 2006). To support this argument, Souiden et al. find that customers

tend to be more loyal to corporate brands than to independent brands. The reason behind this can be the

strong focus of Japanese brands on the “wa” (harmony) in order to make the customer more comfortable

with the brand and gain their trust.

But how will these branding methods work with the Japanese customer in the future? As current sources

on brands are scarce, a short theoretical outlook will be made: As was already noted in the chapter “Outlook

and Possible Changes” the next big trend in the customer market is e-commerce. The main reason why brands

are of high importance online is the factor trust. Customers cannot test, interact, touch and experience

products and services as easily online, which makes trust one of the core decision factors online (especially

if a monetary transaction is involved). Besides customer reviews, a known brand is seen as the core decision

making criteria for a large amount of customers (Nielsen, 2015).

This situation should give established Japanese brands a core competitive advantage in the e‑commerce

arena. But, every positive comes with a negative: The more products are branded with one corporate brand,

the harder it is to control damage to the brand. A high degree of brand diversification therefore might

be the better strategic choice.

Advertising in Japan

As could be seen in the chapter on the Japanese Consumer and Branding Choices, Japanese marketing has very distinct and unique characteristics. The following chapter will first describe the situation in terms of advertising in Japan followed by an analysis of the structure of the advertising market in Japan.

Characteristics of Japanese Advertising

The main characteristic of Japanese advertising besides visual differences in terms of color and ambience is the soft-sell character of Japanese ads (Okazaki, et al., 2010; Johansson, 1994). This implies that the main focus of the ads is not so much highlighting direct product benefits, USP, price or a comparison with the competition, but much more focused on creating an environment that reflects the brand and the ideal experience of using the product. As a consequence, ads are more aimed at the emotional decision maker rather than the rational and function-oriented customer (Tanaka, 1993). In her paper on advertising appeals in the Japanese and American market, Mueller distinguishes soft- and hard-sell the following way:

Soft Sell Appeal: Mood and atmosphere are conveyed through a beautiful scene or the development of an emotional story or verse. Human emotional sentiments are emphasized over clear-cut product related appeals.

Hard Sell Appeals: Sales orientation is emphasized here, stressing brand name and product recommendations. Explicit mention may be made of competitive products, sometimes by name, and the product advantage depends on performance. This appeal includes such statements such as “number one” and “leader.” (Mueller, 1986)

Johansson describes four different approaches that might explain the usage of soft-selling ads in the Japanese market: a

cultural, social, institutional and an economic approach. Each of them will be described shortly in order

to get an impression of the ads and, partially, of the Japanese consumer market (Johansson, 1994).

The cultural argument is mainly based on the relationship between buyer and seller. In Japan, the customer

is not only “king”, but rather “god” and the seller is graceful that the time is spent to consider the

product (Melin & Wikström, 2007). Moreover, the sender of the message is almost sorry to interrupt the

main flow of content (be it a television program or a stream on a web service). In addition, Japanese

education is more oriented towards memorization than rational analysis, thus stating the obvious characteristics

of a product is not as important as creating a memorable mood (Nemoto, 1999, p. 86).

In terms of social persuasion, Johansson argues that the group orientation of Japanese society (Rosenberg,

1986) will lead to more soft-selling advertising. The brand will rather want to build an image of a product

fitting a certain lifestyle and group within society, therefore focusing on the feeling that is connected

with the usage of the product — similar to the western approach of product experience marketing.

The institutional structure of the Japanese advertising industry is another possible explanation for

the lack of hard-selling and directly competing ads. As will be elaborated later in the chapter on the

Advertising Market Structure, the market is focused on a small amount of agencies that have a portfolio

of a wide range of competing products. A hard hitting ad, therefore, is likely to hit a colleague within

the same company, which is not desirable. In addition, the lack of competition within the industry gives

the agencies a position to exert power on the brand owners to push the type of ad that is favorable to

the agency’s interest (Johansson, 1994).

The last explanation that is proposed by Johansson is the economic function of ads in the Japanese market.

Whereas the informational function is seen as one of the core reasons for creating an ad in the West

(Santelli, 1983), this function is often fulfilled at the retail level in Japan. This does not mean,

that certain advertising formats are not used to communicate information to customers, but the likelihood

of this happening is much smaller than in Western, especially the US, markets (Ahmed, 2000, p. 30). This

might also help to explain, why Japanese ads might be perceived as irrelevant from a Western perspective

(Tanaka, 1993).

Advertising Market Structure

As has been mentioned in the previous chapter, the structure of the advertising market in Japan is built around a few core

players. Dentsu and Hakuhodo are the dominating market players, but new online focused companies such

a Cyber Agent are playing catch up (Doland, 2015; Hollow, 2014).

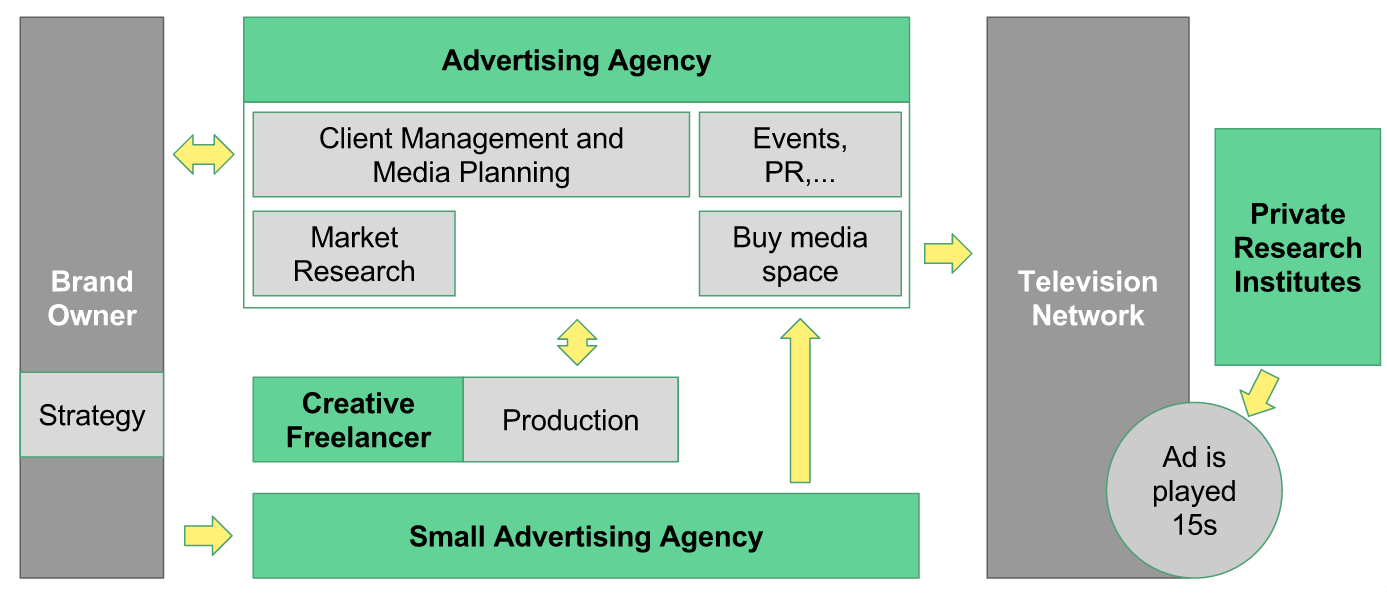

The basic principle behind the structure of the Japanese advertising market is that the big agencies

buy media space in advance, thus locking out all competitors from direct access to the final broadcasting

medium (Mooney, 2000, p. 64). In addition, they have direct and often exclusive access to celebrities

that are of high importance for creating ads in Japan (Hollow, 2014). Coming from this strong position

the agencies are built to be full service providers to brand owners. They have in-house market research,

event planning and even production (although the creative part often is outsourced).

Small advertising agencies have to go through the big agencies in order to place their ads in the media.

Adding to that is the fact that the big agencies also own the market research companies that track the

success of ads.

As the whole industry is built around a few very influential players, there is a very strong and often

long-term relationship between agencies and their clients. This also means that a single agency often

manages several competing accounts. As has been discussed previously, this disincentivises competing

ads, and will hinder the innovation of the business, as a low-cost success of a campaign would lead to

all other clients requesting the same (Doland, 2015). Whether or not the top agencies will be able to

stick to this model when online advertising will be the dominant channel remains to be seen. Access to

media space will not be the core competition factor, but the agencies will be able to benefit from their

long standing relationships with clients and celebrities.

Conclusion

After having described the most relevant aspects of marketing and selling products in the online market, we will now try to give an outlook on where the market is heading. The chapter on distribution systems already showed that a big shift in the market is very likely. With the rise of e-commerce retailers and marketplaces, the current complex distribution system has a very competitive player in their field. B2C shipping is reliable and Japanese consumers are willing to get on board with e-commerce.

B2C shipping is reliable and Japanese consumers are willing to get on board with e-commerce

Even though retailer branding has grown to be of increasing importance in Japan (Dawson & Larke, 2005), the corporate branding efforts of the big companies has secured that their brands are trusted and highly recognized by Japanese consumers. This might be one of the most valuable assets that Japanese companies will have in the online arena. On the other hand, is has been pointed out that damage control is difficult if a brand is connected to a company’s complete portfolio. In the online world, where a single individual can inflict major damage upon a large brand (Deighton & Kornfeld, 2010), this unique strength of Japanese companies might become a weakness in times of crisis.

the media and advertising industry in Japan is very vulnerable to disruption

One thing, that has become very clear, is that the media and advertising industry in Japan is very vulnerable

to disruption. The size and lack of innovation of the big agencies that dominate the business is one

aspect that contributes to this argument. The failure of one of the big companies will then not be able

to be balanced out by the competition, as they lack the resources to manage the vast amount of accounts.

The continuous shift away from television will not help strengthen the position of these companies.

Overall, it can be concluded that most of the special aspects in the Japanese markets have their good

reasons and are based in consumer culture. Even though Japanese firms have a stronghold in their current

offline market, it remains very uncertain if these corporations will be able to stand up to the rapid

development in the online market and possible cultural changes that come with this restructuring of the

market.