What are online business models?

by Max von BeustThis is part 2 of my master thesis on Monetization Strategies and Business Models Behind Consumer Data. Find other chapters here:

2. Business Models

To start with, this chapter gives a short comparative overview of the theory of business models, their different types, and players within these models. It is followed by an analysis of the most prominent monetization models and concludes with the core challenges and opportunities that online businesses are presented with.

2.1 Definition and Logic of Business Models

Although the term “business model” has become ubiquitous in current literature, it is a relatively new phenomenon that has

risen in popularity following the advent of digital companies (Hoffman, Novak & Peralta, 1999, p. 4).

In recent years, academic literature has started shifting its interest from purely web-based business

models to business models in general business (DaSilva & Trkman, 2014, p. 3). Nonetheless, there is no

clear and unifying definition of a business model in current business or informatics literature (Amit

& Zott, 2001, p. 514; Chesbrough, 2002, p. 533; Magretta, 2002, p. 8; Osterwalder, Pigneur & Tucci, 2005,

p. 2; Shafer, Smith & Linder, 2005, pp. 200–202; Sorescu, 2017, pp. 692–694; Teece, 2010, pp. 173–175;

Timmers, 1998, p. 2). Most of the present definitions have three components in common: the description

of how processes and resources are employed to create value in transactions, how this value is delivered

through products and services, and how revenues and costs are managed (Sorescu, 2017, p. 692). The details

of the definitions vary significantly throughout literature.

Timmers (1998, pp. 2–3) describes a business model as the architecture which includes various business

actors, information flows and how these factors contribute to value delivery in the form of a product

or service. In his definition, a business model additionally describes the potential benefits for all

actors within the architecture, including all sources of revenues. In his preferred approach to identify

architectures of business models, he relies on a value chain de-construction and re-construction as described

by Porter and Millar (1985), essentially making a business model the representation of value flows.

the business model is clearly separated from the idea of a business strategy

Chesbrough et al. (2002, pp. 532–535) are less focused on the different actors within a model, but rather

provide a definition of “business model” that describes it as a conversion tool. Technological inputs

are translated into economic outputs in a market environment. The creation of value is seen as a necessary,

but not sufficient condition for a business to benefit from a business model (Chesbrough, 2010, p. 355).

In addition, the business model is clearly separated from the idea of a business strategy (Shafer et

al., 2005, pp. 203–204), as the latter focuses on generating shareholder value and revenues, and takes

competitors into account, whereas a business model is clearly defined with the idea of creating customer

value in mind.

In line with this general idea, Johnson, Christensen and Kagermann (2008, pp. 60–61) see a business

model as the combination of four core elements that create and deliver value to a customer: customer

value proposition (i.e. solving a job for the customer), profit formula (i.e. how to create value for

the company by creating value for the consumer), key resources (i.e. HR, technology and all tangible

assets), and key processes (i.e. value delivery, value flows and scalability). The power of a business

model then lies in the complex interdependencies or value streams between these components.

Osterwalder, Pigneur and Tucci (2005, pp. 2–7) take a step back and approach the definition of a business

model as the combination of model (i.e. “a simplified description and representation of a complex entity

or process” Wordnet 2.0, 2003) and business (i.e. “the activity of providing goods and services involving

financial, commercial and industrial aspects” Wordnet 3.1, 2018). Thus, they describe a business model

as the conceptual tool containing all elements of a business and their connecting logic that enables

a firm to deliver value in a profitable manner within the firm's current network of partners. In a later

revision, Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010, p. 14) define a business model more broadly as “the rationale

of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value”.

By compiling all the previous definitions, Da Silva and Trkman (2014, pp. 2–5) provide a theoretical

framework to deduce a definition for business models. They propose combining a resource-based view with

the theory of transaction cost economics, as business value is a combination of these components (Morris,

Schindehutte & Allen, 2005, pp. 727–730). Thus, business models are defined as a combination of resources

which generate value for both, customers and the organization, through specific transactions, which create

cost. This transaction-, value- and resource-based definition will be applied for the current thesis

as it is the most comprehensive combination of theories with a clear focus on value creation in the interaction

of players.

business models are defined as a combination of resources which generate value for both, customers and the organization, through specific transactions, which create cost

2.2 Types of Business Models

As a logical continuation of the definition of business models, several types of models have been identified. As there have

been many different attempts of classifying business models or creating a clear taxonomy (Rappa, 2004,

pp. 34–38), this overview does not aim to be exhaustive and other classifications might be more suitable

for other use cases. There are two prominent ways of deriving different types of business models: The

first is a resource or value chain perspective (Timmers, 1998, p. 2), the second is a transaction or

environmental perspective (Eisenmann, Parker & van Alstyne, 2006, pp. 2–4).

Following the first perspective, Timmers (1998, pp. 8–10) introduces two dimensions for distinguishing

different models in one of the first classifications of electronic business models: the degree of innovation

and the integration of functions within the value chain. As was noted earlier, business models were first

associated with web-based business and later applied for all businesses, as a broad range of technologies

and methods employed by web-based companies were adopted by a wide range of industries (Porter, 2001b,

p. 73). In line with the second dimension of integration, we can derive three types of business models

(Teece, 2010, p. 184). These three business models based on function integration and value chain position

will now be discussed briefly.

The first and most obvious type is a model built upon full integration of all parts of the value chain.

This integrated business model type is fully responsible for product and service design, manufacturing

and distribution. A business area where this type of model has been prevalent to the present day is in

the petroleum industry, where companies own natural resources (and/ or extraction rights), their exploitation,

processing, distribution and marketing (Hewitt, 1960, pp. 259–273; Stacey & Crooks, 2016). On the opposite

part of the spectrum we can find the outsourced or fully-licenced approach where a company does not own

any part of the value chain, except for specific intellectual property rights, which enables a crucial

step within the process of creating value. A traditional example of a purely licensing-based business

is ARM with their processor design which they licence to chip manufacturers in exchange for royalties

(Goodacre & Sloss, 2005, p. 43). Nonetheless, by far the majority of business models can be identified

as a hybrid type. They are a part of the overall value chain or own several parts of the value chain.

Although it can be argued that online models have started converging towards greater integration (Thompson,

2015), full ownership is rarely seen. Organizations applying hybrid approaches have to take into account

a larger variety of different resources, processes and stakeholders and often are identifiable by an

exceptionally strong selection of management skills (Teece, 2007, pp. 1346–1347).

Although it can be argued that online models have started converging towards greater integration, full ownership is rarely seen

Within the types presented, value is still flowing between revenue and cost in one direction in the value

chain (Porter, 2001a, pp. 50–51). In contrast to these one-sided business models, two-sided models have

costs, revenues and distinct user- or customer-groups on both sides of the model. Whereas the former

are often seen as the classical example of a business, the latter are commonly known as platform business

models and are based on an analysis of environmental and transactional aspects as proposed by Eisenmann,

Parker and van Alstyne (2006, pp. 2–4).

Following the perspective proposed by Eisenmann (2006, pp. 2–4), a central characteristic of these platform

business models are their cross-side network externalities between two or more different types of participants

(Bakos & Katsamakas, 2008, pp. 171–174). Both sides in this model are needed to succeed, which often

leads to it being identifiable by a “money side” and a “subsidy side” (Eisenmann et al., 2006, p. 3).

The participants on the “subsidy side” are often attracted to create a certain volume attracting financial-value-generating

participants on the “money side”; this can be the solution to the “chicken-and-egg problem” two-sided

models face.

a central characteristic of platform business models are their cross-side network externalities between two or more different types of participants

Putting all the parts together, we can find two major types of business models: one-sided and two-sided platform models. Whereas the latter has emerged in recent years, the former and more traditional type can be divided into different subtypes based on their role within the overall industry value chain and system.

2.3 Players in Online Business Models

To further deepen the understanding of business models in a web or online environment, different core actors within the majority of current online business models are described. As has been noted earlier, this overview will not be exhaustive and the importance of different players will differ for each model. The goal, however, is to create a general understanding of certain terms and players and their importance for the current topic. This section will describe the three main players in the online business models: the business, the customer, and the partner.

2.3.1 Business

The central part of all online business models is the business as a commercial operation or company. It serves as a creator of consumer value (Eggert & Ulaga, 2002, pp. 108–110), a mediator between actors, incurs costs and ideally generates revenues. The main challenge for the business is to create a product and find a fit in the market with the right business model and strategy (Zott & Amit, 2008, p. 2). According to Heim (2016, p. 286), in the context of online business, a product can be understood as a physical good, an offline service or any kind of digital value delivery - or a bundled combination of these components. Achieving a product-market fit means finding an attractive market or customer segment which requests (and indirectly improves) the product the company can build with the available resources (i.e. capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, capital, people and all other assets) (Andreesen, 2007; Barney, 1991, p. 101).

The main challenge for the business is to create a product and find a fit in the market with the right business model and strategy

Overall, an online business differs from a traditional company beyond the change of environment and market it operates in. Not only does an online business use online transactions and value delivery at some point of the customer interaction for revenue generation, but the “online” aspect of doing business has implications for internal characteristics as well. Online businesses strive to build user centric products (e.g. through personalization), integrate user interaction (e.g. A/B testing) and have short cycle times supported by decision making on all organizational levels (e.g. by product managers). Further aspects and challenges in these businesses will be discussed later. (Ng, 2017; Wirtz, Schilke & Ullrich, 2010, pp. 276–279)

2.3.2 Customer

Finding an accurate definition of a “customer” in literature can be challenging as most authors assume that the term is clearly

defined and fully comprehensible. Nonetheless, several authors use the terms “customer” and “consumer”

as direct synonyms (Cronin, Brady & Hult, 2000, p. 194; Gambetti & Graffigna, 2010, p. 802; Iacobucci,

Ostrom & Grayson, 1995, p. 276; Rose, Hair & Clark, 2011, p. 1).

The simplest way to identify a customer is to look at financial transactions. Every entity that pays

money to a business in return for (perceived) value is a customer, no matter if this is an individual

or an entity. Customers are purchasers and do not necessarily have to have the intention of using or

consuming a product, service, or any other value that is provided by the business (Joseph, 2012). In

contrast, consumers are the actual users of a product or service and do not have to be involved in any

financial transaction. In business-to-consumer environments, consumers are often involved in the financial

transaction, thus being customers as well - as can be seen from the term “Customer Relationship Management”

(CRM) which often refers to customer and consumer management.

2.3.3 Partner

In online environments, it has become increasingly difficult to draw a clear line between a consumer of a service and a customer

of a service. This challenge becomes clear when describing the different stakeholders that are involved

in an online advertising business. The financial transaction for placing an ad in a search result has

a (business) customer as a source and is received by Google.

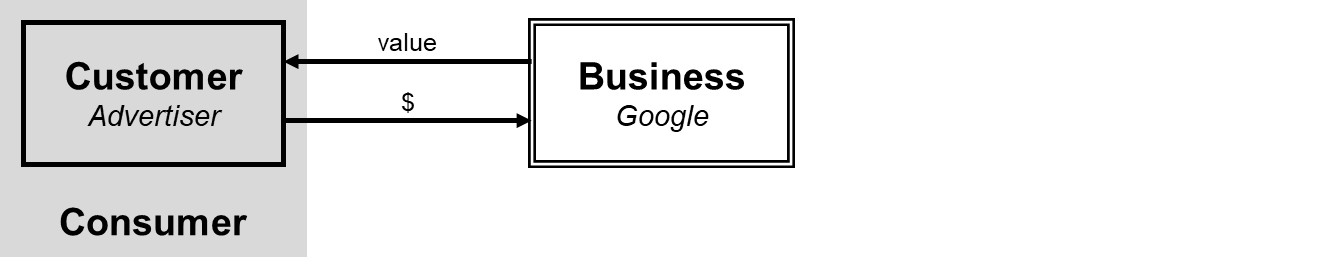

Google can be recognized as the business in this case. The advertiser - the entity that is the source

of the financial transaction - is the customer. This leaves us with a situation (see Figure 1) where

we have clearly identified a business and a customer that receives value from the business, thus is a

consumer at the same time. Nonetheless, Google relies on another core group for their offering: the users

of the search engine.

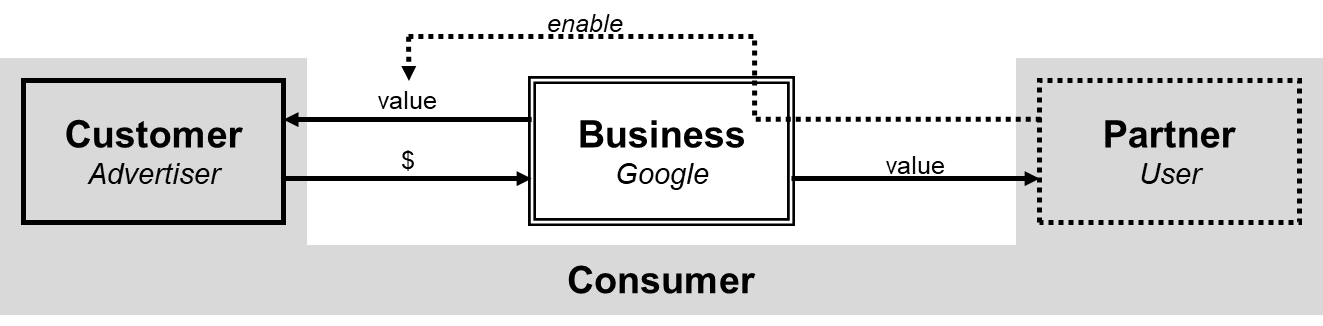

The information that Google collects about the user and the access to a user that Google can provide to its customer, are core to the success of the business model. In order to attract the user, Google offers value (by providing a search engine) to the user without receiving direct financial value from the user. In this case, the user clearly is not another customer, as no financial transaction has occurred. It is not a pure “resource” either, as value is provided by Google to the user. In order to solve this ambiguity, the person or entity receiving value from a company without being involved in a direct financial transaction is described as a “partner” to the business as seen in Figure 2.

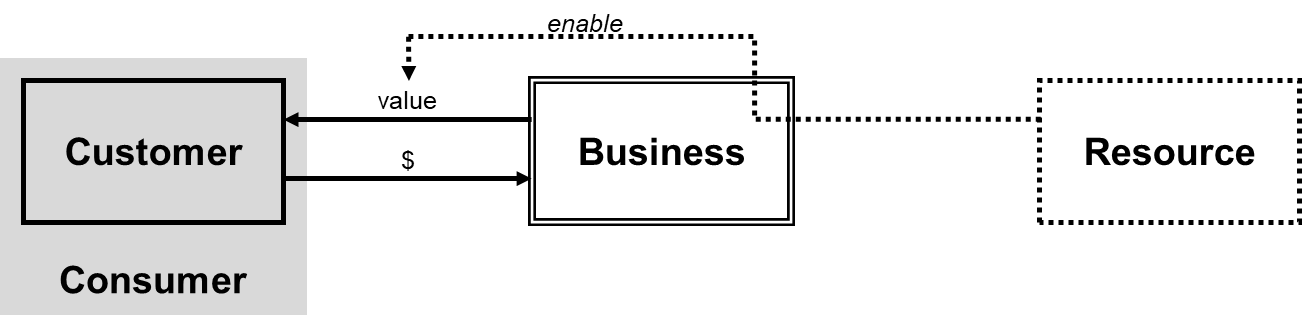

Should the business not provide any value to the individual, then this case shall be described as a "resource" to the business. This "resource" is neither a customer, nor a consumer, nor a partner. In the model of a classical data-broker which is collecting and selling data about individuals without providing any benefit to the individual, the latter is a “resource” as seen in Figure 3. Partner and resource alike can be essential to the revenue generation of the business.

Continue with: