How Can You Make Money Online?

by Max von BeustThis is part 3 of my master thesis on Monetization Strategies and Business Models Behind Consumer Data. Find other chapters here:

2.4 Online Monetization Models

To get a better understanding of online financial transaction models, or monetization models, the following chapter will provide an overview of the most prevalent models. These models are not mutually exclusive, as most of them can be and some have to be combined to be effective. Monetization models are also sometimes referred to as business (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, p. 46) or revenue models (Cornell, 2012; Johnson et al., 2008, p. 60). The underlying idea of monetization models is to translate provided value into financial gain. Throughout the section, the five most important online monetization models will be discussed. Firstly, the advertising model will be discussed in more detail. Secondly, the subscription model will be explained. Thirdly and fourthly, the relatively new freemium and pay-per-use model will be discussed. Finally, this section provides an overview of the e-commerce model which is comparable to traditional business models.

2.4.1 Advertising Model

The first, and potentially most influential model, is the advertising model. Global spending for online advertising has been increasing steadily with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.4% in the past 10 years, clearly demonstrating the prevalence and importance of advertising as a medium of monetization (Silverman, 2017). This trend has the potential to be a reality for an extended period of time: in 2016, only 25% of all European businesses were using online advertisement (European Union, 2017), compared to 75% of US small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Though the European market has great potential to grow using this model, the advertising-based models are already the engine powering a large amount of websites and online businesses (Clemons, 2009, pp. 15–18).

in 2016, only 25% of all European businesses were using online advertisement, compared to 75% of US small and medium enterprises

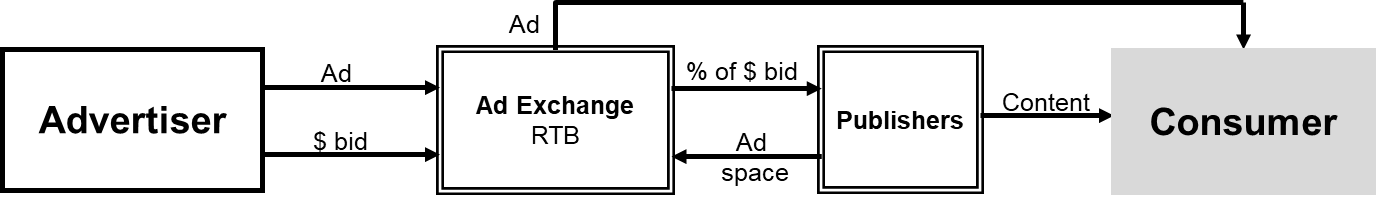

The basic structure of online advertising models is similar to the way newspaper models work (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, p. 46): An advertiser pays a publisher in return for ads shown to the consumers that are attracted by the content the publisher. In the traditional newspaper business, the publisher (such as a newspaper, magazine, etc.) sells and publishes the ads provided by the highest bidding advertiser as seen in Figure 4.

This system has been translated directly to the web by companies such as Altavista and Yahoo (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, pp. 46–47)

and has been improved upon by Google and Facebook with their advertising offerings Google Adwords and

Facebook Ads respectively. In continuation of the traditional model, Facebook and Google act as publishers

themselves, although they only aggregate content on their own platforms. The true innovation, however,

lies in the sophisticated systems that these companies have developed in order to evolve into ad exchanges

as well, integrating more business functions into their own business model (Balseiro et al., 2014, p.

1).

An ad exchange tries to place ads accepted from advertisers as attractively as possible for its clients.

This new model outsources the ad acquisition and allocation job previously done by the publisher to the

ad exchange. In order to fulfill its task, an ad exchange collaborates with as many publishers (e.g.

blogs, websites) as possible (through an online offering such as Google Adsense or Facebook Audience

Network), which offer ad space to the exchange and attract consumers with their content (Negrini, 2016).

The underlying monetization model and financial flows are depicted in Figure 5.

Ad space can be offered in several different forms across all distribution platforms by the publisher

e.g. banners, buttons and videos. A publisher then is able to monetize their offering through the percentage

of the bid of every ad that is placed on their website by the ad exchange - the exact share the publisher

receives depends on the performance of the specific ad. Which ad is displayed in which specific situation

is decided by real-time bidding systems (RTB) which compare ads based on their fit for the specific consumer

and the potential earnings for the publisher (Yuan, Wang & Zhao, 2013, pp. 1–3). The online advertising

model is a monetization model for both the publisher and the ad exchange, with the advertiser as the

customer and the user as the consumer.

Overall, the basic methods of the advertising model are similar for all types of online advertising,

although the details of revenue generation and placement systems can vary significantly (e.g. cost-per-mille,

pay-per-view, affiliate...).

2.4.2 Subscription Model

With the subscription model, a particular customer does not get a service for free, instead he gets charged a fixed amount of money on a regular basis (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, p. 47; Weinhardt et al., 2009a, pp. 31–33). The customer can use a predefined selection of services or service components for a fixed amount of time - commonly per month or per year. Subscription fees are charged on an ongoing basis without taking the actual usage into account (Rappa, 2004, p. 37). This can lead to the problem that customers use the service more frequently at a higher total cost than predicted by the business.

a great advantage of the subscription model, to both customer and business, is the high predictability of cash-flow

One of the main challenges of the subscription model is that a product or service must appear valuable and

distinctly different from more convenient (or even free) alternatives - a commonly known example of this

problem are paid online news offerings (Chyi, 2005, pp. 140–141). In contrast, a great advantage to both

customer and business is the high predictability of cash-flow.

Although subscription models have their roots in the publishing business, all kinds of service companies

are starting to implement this monetization model - from utilities to retail. As product-based businesses

are converging towards service models, the subscription model is often seen as a viable method of monetization

(Wille, 2017) and its popularity has been increasing steadily (Segran, 2015), albeit with widely differing

success (McCarthy & Fader, 2017).

2.4.3 Freemium Model

Although the term “freemium” has only been coined recently by Wilson and Lukin (2006), the concept of freemium monetization has been common in online service businesses since the 1980s (Wilson, 2006). The basis of the freemium model is to combine the provision of a service for free with a “premium” revenue-generating model. The “premium” part of the service offers additional value to the customer based on a monetization model, whereas the base offer enables the consumer to perceive enough value to continue using the service. The motivation for a business to use this monetization model is to create a broad funnel which then leads more customers to the secondary monetization model. (Kumar, 2014)

frictionless distribution in the freemium model increases the probability of adopting a service

The wide-range adoption of the freemium model was enabled by digitalization which led to higher distribution

speeds and significantly lower distribution cost (Seufert, 2014, pp. 1–2). In addition, the freemium

model now has been expanded to a “paymium” model, where customers pay for basic features and are then

charged for additional functionality (Lescop & Lescop, 2014, p. 6).

This frictionless distribution in the freemium model increases the probability of adopting a service,

as the consumer does not have to bear any financial cost. For example, a service such as Dropbox is free

to use and consumers can start using the service at no financial cost, only upgrading to the next phase

of monetization when certain storage limits have been reached (Balaji, 2015).

2.4.4 Pay-Per-Use Model

The pay-per-use or utility model might be the most prominent model in the cloud computing environment, where customers pay a fixed amount for every predefined unit that is consumed (Weinhardt et al., 2009a, p. 32; Weinhardt et al., 2009b, p. 396). Unlike monetization through a subscription, pay-per-use is based on metering usage (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, p. 47; Rappa, 2004, p. 37). Although this model is the most transparent one and reflects actual usage in the most accurate way, the clear disadvantage is the lack of predictability when it comes to cash-flows, which can lead customers to prefer fixed-price models such as subscriptions (Fishburn & Odlyzko, 1999). Often, pay-per-use models are billing usage over a longer time-span and barely ever only include a one-time transaction of value.

2.4.5 E-Commerce Model

Electronic commerce can simply be understood as the electronic way of doing business. In the context of monetization models

however, the idea is to sell products to customers in online environments which are then provided either

on- or offline (Timmers, 1998, p. 3). Previously, this model was known as e-shop, e-mall, e-auction or

merchant model (Afuah & Tucci, 2001, p. 47; Timmers, 1998, p. 5). Rayport (1999, p. 7) argues that the

basic idea of monetization through e-commerce is the accumulation of a large amount of potential customers

who then are converted into profitable customers through methods such as cross- or upselling. The customer

pays for an individual product or service and not the explicit usage of this product or service.

In essence, the e-commerce model does not differ from the usual commerce model as there is a unique financial

transaction between the customer and the business in exchange for a (physical) good. This financial model

can be based upon fixed prices or auctioned prices. The business does not have to be the manufacturer

or provider of the good, but can facilitate the purchase, as a retailer would do in customary commerce.

Thus, monetization happens through a specific margin that is made on the sale of an individual product.

2.5 Core Challenge and Opportunities in Online Monetization

The previous chapters gave an overview of the prevalent options for businesses to successfully monetize their offerings to consumers and convert them into customers. Nonetheless, a large amount of businesses are failing to generate sustainable profits (Demos et al., 2015; Hook, 2017) or even are unable to start business due to a lack of cash-flow (Iskold, 2008). One of the core reasons for this observation is the basic economic phenomenon that in a market with perfect competition, prices will equal marginal cost (Stigler, 1957, p. 5). With the marginal cost of digital goods and services approaching zero, companies are able to provide value to consumers without requiring a financial transaction (Anderson, 2008; Rifkin, 2014). Unless a company has a monopoly or a high lock-in effect, users will have the option to migrate to a different service as switching costs have decreased as well. The price elasticity of demand for these products is close to infinity with a horizontal demand curve at the price zero - this implies that consumers request as much of the product as possible at the current price, but switch to an alternative with the first price increase (“The penny Gap” Kopelman, 2007) (Chyi, 2005, p. 133). The outcome that can be observed is the tendency of customers to take it for granted that a digital product or service is free and that their willingness to pay for services online decreases (Regazzi, 2014, p. 68; Teece, 2010, p. 172).

a large amount of businesses are failing to generate sustainable profits or even are unable to start business due to a lack of cash-flow as customers take it for granted that a digital product or service is free

Compared to the pre-web economy, the core challenge of internet-based businesses is to extract value from consumers in order

to turn them into valuable stakeholders for the company. As pointed out above, the most important value

transaction, namely the financial one, is disappearing. Companies have to seek alternative models to

transmit value from a consumer to the business. In the following paragraphs, three alternative value

propositions of consumers are presented: network, content and data.

Network

The main theory behind current social networks is the network effect, where the usage of the product

by an additional consumer increases the value of that product for both consumers and the business providing

the product (Katz & Shapiro, 1994, p. 99). A consumer creates value for the business simply through presence,

which establishes a network upon which traditional monetization models can thrive (Domingos & Richardson,

2001, p. 57; Jorgenson, 2015). Most online communication tools nowadays are fully dependent on the presence

of a large amount of consumers as value, and hence potential for monetization is only created in the

interaction between parties.

Content

In addition to providing value through their presence alone, consumers can also be creators and providers

of value through the content they produce. A common example are social networks such as Facebook or Instagram,

but also publishing platforms such as Medium or the “Shot on iPhone” campaign by Apple (Hunegnaw, 2017).

A lot of platforms have full usage rights of the user-generated content (UGC) and can monetize it directly

or indirectly on this basis (Facebook, 2015; Instagram, 2017; Smolar, 2010). This movement has led to

the creation of the term “prosumers” for consumers who are producers at the same time. Companies benefit

from prosumers as their content directly adds to the business value which enables countless monetization

opportunities (e.g. advertising Athsani et al., Yahoo! Inc, Patent No. US 8,655,718 B2, 2013). (van Dijck,

2009, pp. 42–46)

Data

The one resource that consumers have increasingly been creating in recent years is data about their

lives and environments. As the rate of private data-related interactions is predicted to increase 20-fold

in the next 10 years, the potential value created on this basis will rise significantly (International

Data Corporation, 2017, p. 14). Companies already are competing for access to consumer data (and potential

secrets) with the goal of extracting additional value and revenue (Ohm, 2012).

the rate of private data-related interactions is predicted to increase 20-fold in the next 10 years

Consumer data has long been described as the resource that will dominate the current century as much as oil dominated the previous one (Naughton, 2013; Palmer, 2006). The main question that remains is where the opportunities lie in the data economy and if these opportunities can be a solution to the challenge of the penny gap or provide for new ways of generating consumer value. How will businesses be able to create additional value for consumers, generate revenues or provide products at the lowest possible price to private consumers by harnessing the power of consumer data?

Continue with: